“David Burliuk and the Japanese Avant-garde” was released on DVD in the autumn of 2007. The film charts the work of the Russian futurist David Burliuk in Japan. After he left Russia during the Russian civil war, David Burliuk spent two years in Japan and put on exhibitions in Tokyo, Kyoto and Yokohama. His influence on the growing Japanese futurist movement was immeasurable where he worked with Japanese artists such as Kinoshita and Murayama. The film features locations in Moscow, Tokyo, Kyoto and a small Island called Ogasawara in the Pacific Ocean which Burliuk visited in the manner of Gauguin. Japanese art was was gradually transformed in the Meiji period of the late 19th century and early 20th century after the Meiji restoration which heralded Japan’s entry onto the global stage.

“David Burliuk and the Japanese Avant-garde” was released on DVD in the autumn of 2007. The film charts the work of the Russian futurist David Burliuk in Japan. After he left Russia during the Russian civil war, David Burliuk spent two years in Japan and put on exhibitions in Tokyo, Kyoto and Yokohama. His influence on the growing Japanese futurist movement was immeasurable where he worked with Japanese artists such as Kinoshita and Murayama. The film features locations in Moscow, Tokyo, Kyoto and a small Island called Ogasawara in the Pacific Ocean which Burliuk visited in the manner of Gauguin. Japanese art was was gradually transformed in the Meiji period of the late 19th century and early 20th century after the Meiji restoration which heralded Japan’s entry onto the global stage.

Perceptions of Japan as a closed and traditional society changed in the aftermath of the Meiji restoration. There was a Rush to modernize and industrialize Japanese society. Some artists were beginning to recognize the hegemony of industrial society and its profound implications for art and culture. It spawned a counter culture in Japan with a tendency to rebellion by those who saw in modernism a progressive opportunity but also its tendency for alienation. However it was Burliuk who translated to Japanese audiences developments in Russian art .

After just two weeks in Japan he had organised an exhibition in Tokyo entitled “The first Exhibition of Russian Paintings in Japan” which opened on Oct 14th at the Hoshi pharmaceutical head quarters in Kyoboshi. There are few records left of this exhibition but reviews described astonishing works of dangling socks and matchboxes attached to paintings and painting rendered on cardboard.

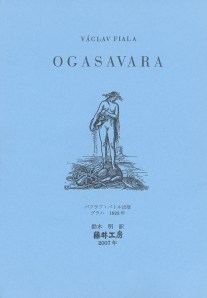

Part of the film involved visiting an island called Ogasawara  which is situated in the Pacific Ocean about 1000 kilometres south of Tokyo. The Journey takes around 26 hours and can only be reached by ship.

which is situated in the Pacific Ocean about 1000 kilometres south of Tokyo. The Journey takes around 26 hours and can only be reached by ship.  Burliuk visited the island and spent about three months there painting and relaxing after his mammoth journey through Siberia and onto Japan and the various exhibitions in Tokyo and Kyoto. It made a warm change from the icy blasts of a siberian winter. I had already decided that I would follow Burliuk’s journey to this island as well as film in Tokyo and Kyoto. I had already completed half the journey, albeit on a comfortable flight from Moscow to Tokyo. Now it was time to go all the way, as far as Burliuk himself went.

Burliuk visited the island and spent about three months there painting and relaxing after his mammoth journey through Siberia and onto Japan and the various exhibitions in Tokyo and Kyoto. It made a warm change from the icy blasts of a siberian winter. I had already decided that I would follow Burliuk’s journey to this island as well as film in Tokyo and Kyoto. I had already completed half the journey, albeit on a comfortable flight from Moscow to Tokyo. Now it was time to go all the way, as far as Burliuk himself went.

Burliuk was a keen student of Japanese culture and much like his idol Gauguin he immersed himself in Japanese culture and art. Interestingly enough Burliuk’s Journey to Ogasawara began when he left by ship from a point not far from where Basho started his travels in old Edo the former capital of Japan which became Tokyo. Basho was another wanderer poet much like Burliuk who was destined to travel throughout the world seeking new inspiration for his art and life.

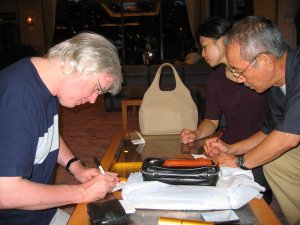

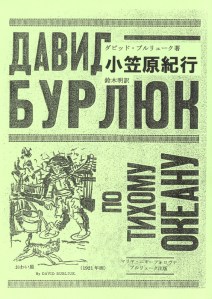

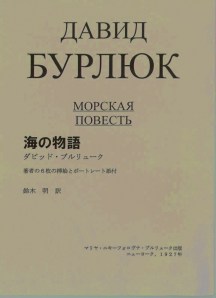

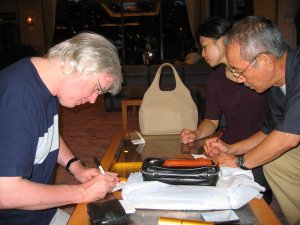

I wasn’t sure how the Ogasawara material would relate to the rest of the film. In fact sometimes I doubted the wisdom of going there at all. This all changed after my interview with Akira Suzuki. A friend of a friend recomended me to interview him as a Japanese expert of Burliuk’s time in Japan in general. He writes about Burliuk’s work and art and translates his books from Russian into Japanes He as published several translations of Burliuk’s writings from Russian into Japanese as well as a number of books about Burliuk and Fialev, the Czech artist who traveled to Japan and Ogasawara with Burliuk. (Follow this link for more information about Akira Suzuki’s work).

Akira Suzuki turned out to have a wide knowledge of Burliuk’s life and work in Japan, which very few people would have known if any at all. This inside knowledge and understanding proved invaluable for the film. This was especially true when he explained how Burliuk wanted to visit a south sea island and spend time painting there much like Guaguin. This was the reason he visited Ogasawara. Suddenly many things fell into place and I understood why Ogasawara would be important to the film and indeed the series about the Russian avant-garde overall. Burliuk was the Father of Russian futurism and was heavily influenced by Guaguin as was much of the Russian avant-garde itself either through Burliuk’s influence or generally through other artists.

Akira Suzuki turned out to have a wide knowledge of Burliuk’s life and work in Japan, which very few people would have known if any at all. This inside knowledge and understanding proved invaluable for the film. This was especially true when he explained how Burliuk wanted to visit a south sea island and spend time painting there much like Guaguin. This was the reason he visited Ogasawara. Suddenly many things fell into place and I understood why Ogasawara would be important to the film and indeed the series about the Russian avant-garde overall. Burliuk was the Father of Russian futurism and was heavily influenced by Guaguin as was much of the Russian avant-garde itself either through Burliuk’s influence or generally through other artists.

Guaguin himself when searching for a new form of art drew upon Japanese art as a way of discovering a new style or a new direction in art. As he said himself “artists have lost, ……all their instincts, one might say their imgaination and so they have wandered down every kind of path in order to find the productive elements they hadn’t the strength to create”. Gauguin was the first European artist who consciously sought to synthesis the expressive means of various epochs and peoples with European artistic techniques, in particular the Japanese, opening up new possibilities for painting and art.

Burliuk also was forever seeking new rhythmical structures and innovations in his work, simple solutions for expressing new ideas and phenomena. In this the Japanese artistic values of the ornamental organisation of the surface of the canvas would provide him with ample material for study.

Akira Suzuki explained how Burliuk not only organised exhibitions and gave lectures, he thoroughly familiarized himself with Japanese life. He took care to understand a complicated culture full of diverse subtleties and nuances. Burliuk tried to penetrate the meaning that lies embedded in the aesthetic life of Japanese culture and art much like his idol Gauguin.

The importance of Gauguin for Burliuk cannot be underestimated. Gauguin was a precurser of the 20th cnetury avant-garde movementas a whole. His independent and bold search for a new form of art had an enormous influence on the development of the decorative principles of the Russian avant-garde. Far from the turmoil of civil war and revolution Burliuk believed he could live and work in an environment of relative safety.

All at once, talking with Akira Suzuki, the themes of the Russian avant-garde, David Bulriuk, Guaguin, Japan, Japanese futurism and a south sea island merged into something concrete and understandable in the context of a film and in particular a film about Burliuk and his relation to Russian and Japanese futurism.

From his writings we can imagine Burliuk’s thoughts as in the early morning light the ship approached Ogasawara. Coming out on deck he could gaze on the fantastic sight of an island he had never seen before.

Akira Suzuki was a knowledgable and relaxed interviewee. The thing I liked most about him on screen is his easy and friendly delivery. I had the choice of interviwing him in English or Japanese. In the end I went for the Japanese with English subtitles as his enthusiam and excitement for the subject comes through when speaking in his own language. This was exactly the mood I wished to create in the film and in this Akira Suzuki helped me a great deal. The things he knew about Burliuk had a personal quaility about it, one could feel that he had a strong attachment towards Burliuk and a feel for the subject as well as having engaged in the research. His anecdotes and stories about Burliuk in Japan could only have come from sources close to the Japanese.

On a later visit to Japan Akira Suzuki took myself and my wife Natalia to the very place where Burliuk boarded ship to Ogasawara. It is a quiet stretch of water in the heart of Tokyo. Later the same day he took us to a nearby region where the Hakia poet Basho lived and composed his poetry and from where he set off on his journeys around Japan seeking inspiration and enlightenment. I couldn’t help thinking of Burliuk who set off not very far from the spot where Basho undertook his spiritual journeys around Japan and wondering if Burliuk felt any connection with the great poet of Japanese literature given that Burliuk was as much of a poet as he was a painter.

A few days later Akira had another surprise waiting for us. He asked me would I like to see an original painting of David Burliuk which a friend of his had in his possession. Of course we jumped at the chance. The next day we arranged to meet and we all travelled by metro to Ikejiri-Ohashi.

A short walk from the station was a small modest shop-front gallery overshadowed by one of those giant exressways which are raised above the city on tall thick columns and criss cross Tokyo. We went inside and were introduced to a gentle mannered man in his late 50s who owned the gallery.  After some tea and getting to know each other he brought out a cardboard carton and gradually took off the wrapping to reveal a beautiful unframed canvas of a village on Oshima in 1920 which Burliuk painted on one of his visits to the island. For the first time I realised why some people want to collect or horde great works of art. The magic of being close to something or someone through their work was literally breathtaking, especially somebody who I had been researching for so many months. It felt like small currents of electricty running through my spine. I thought I had come to know Burliuk quite well but gazing at a work of art which had been painted in Japan and

After some tea and getting to know each other he brought out a cardboard carton and gradually took off the wrapping to reveal a beautiful unframed canvas of a village on Oshima in 1920 which Burliuk painted on one of his visits to the island. For the first time I realised why some people want to collect or horde great works of art. The magic of being close to something or someone through their work was literally breathtaking, especially somebody who I had been researching for so many months. It felt like small currents of electricty running through my spine. I thought I had come to know Burliuk quite well but gazing at a work of art which had been painted in Japan and which I could pick up and look and touch and feel, was a very different experience from seeing something in an art gallery and moreover by an artist of such stature in the Russian avant-garde. When I turned the painting round to look at the back, there in faded Russian and Japanese, was written, that the painting had been exhibited in the “First Exhibition of Russian Painting in Japan”. I and Natasha examined the painting for maybe half an hour. It was an experience that I didn’t really expect, in so far as looking at a painting can be such an energising event. It is something which is difficult to put into words

which I could pick up and look and touch and feel, was a very different experience from seeing something in an art gallery and moreover by an artist of such stature in the Russian avant-garde. When I turned the painting round to look at the back, there in faded Russian and Japanese, was written, that the painting had been exhibited in the “First Exhibition of Russian Painting in Japan”. I and Natasha examined the painting for maybe half an hour. It was an experience that I didn’t really expect, in so far as looking at a painting can be such an energising event. It is something which is difficult to put into words

The second half of the film is about Burliuk’s influence on the Japanese avant-garde itself which was considerable. After he emigrated finally to America with his family the legacy of his time in Japan continued to live on and influence Japanese futurist artists like Kinoshito and Murayama who had a strong influence in all areas of Japanese cultural life – literature, architecture, the visual arts,

design and to a large extent theatre.

The explosion of passions was reflected in the two exhibitions оf the Sanka association, in the second half of September 1925. Because “Sanka in the Theater” attracted wide attention, the exhibition was crowded with more visitors than the organizers had expected. Augmented by an extra 122 works, this exhibition was the largest оf the avant-garde movement. Disparate media and subjects scandalized the public: а Dadaist assemblage of two ropes entitled Lumpen Proletariat А апd B was executed by Toki Okamoto who had come to the gallery and made it on the spot; the entrance tо the gallery was decorated by а large, three-dimensional hybrid assemblage; apart from these Dadaist pieces, some pure geometric works were also shown.

The exhibition was an experiment, a scandal and a social event.

The Japanese avant-garde attempted to cut across two opposing trends in Japanese art. The national traditionalist approach in art and the westernization of art which had gripped Japanese culture. Informed by Burliuk’s experiments and their own innovations they searched for new art forms which would liberate them from the confines of these two trends.

Burliuk conceived elements of surface plain, texture and colour as tangible elements in painting asserting the two dimensionality of the picture surface. Such bold experiments in painting were readily taken up by Japanese futurism and the avant-garde in general giving the innovations of Japanese artists a global outlook and focus at a time when Japan was still emerging from a period of isolation and coming to grips with industrialization and its social consequences.